Executive Summary

Perhaps the most common, and most important, forms of rapid thought we have are the judgments we make about other people. Upon meeting people, we make countless conclusions about what they are thinking and feeling, and make predictions about what they will do or say next. This is human nature and universal. However, when interacting cross-culturally, these conclusions can often be misleading and the assumptions we make can be wrong, sometimes with drastic effects. For example, consider the salesperson who misunderstands agreement as a buying signal, only to lose a sale that seemed a sure thing. Or the manager who concludes that he or she has made task objectives clear to an employee and later, after the deadline has passed, finds out that the employee has been waiting for more direction.

Wilson Learning Worldwide has had the great fortune to examine how people around the world make judgments about interpersonal preferences and style. In over 30 countries and cultures, our research shows that people who are skilled at identifying Social Style and adapt their behavior to make others feel more comfortable perform better and are more successful. We call this skill Versatility. For Wilson Learning, and many of our clients, Versatility is one of the key skills for success in business today.

In this report, we examine the similarities and differences across cultures in Social Style and interpersonal Versatility. The results of our research demonstrate that:

- The four Social Styles exist and can be accurately measured in every country examined.

- Cross-culturally, the Social Styles are similar in the behaviors and characteristics people use to define them.

- Versatility, as well as being linked to success within the individual cultures, is also linked to characteristics associated with effective cross-cultural relations.

This report provides convincing evidence that interpersonal Versatility could be a key factor in the development of effective global business alliances, and may in fact be a determinant of the global effectiveness of different cultures.

What Is Social Style and Versatility?

There are two things almost all people know about their relationships with other people:

- All things being equal, we really only “connect” with about 25% of the people we interact with.

- It is easier to communicate with those with whom we “connect.”

When people say they “connect” with someone, they are referring to the similarity of their communication preferences and styles. We feel more comfortable with people who like to talk at the same pace we do, who are not too pushy or too pliable, and who want to get to know about us at about the same time we are ready to share that kind of information.

Nearly half a century of research has shown that people are divided equally across four primary communication styles. These four Social Styles are called Driver, Expressive, Amiable, and Analytical. When you find a person is easy to work with, it is often because you share the same Social Style. When a person seems difficult to work with, it is often because your styles are different.

Wilson Learning has also had the opportunity to test the validity of Social Style globally. Sometimes driven by our own desire to share the technology with other cultures and sometimes driven by the needs of our global clients, we have developed and validated the primary tool for measuring Social Style and Versatility, the Social Style Profile, in over 30 different nations on six different continents. Now we feel we have sufficient data in our Social Style Profile database to draw some meaningful conclusions about the global nature of Social Style and Versatility.

What the Social Style Profile Measures

The following is not a full description of the Social Style model; rather, it describes briefly the four dimensions that are measured by the Social Style Profile.

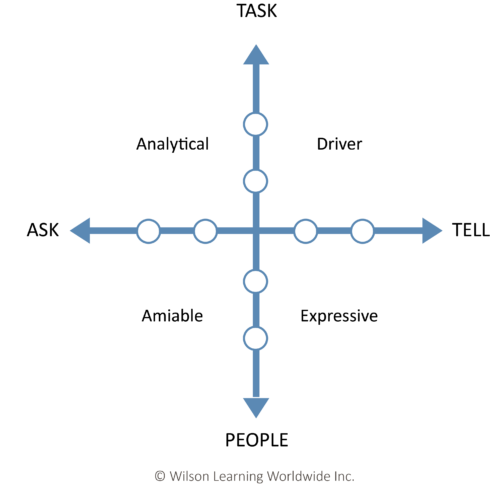

Assertiveness is defined as the way a person attempts to influence others’ actions and decisions. At one end of the scale, people are “Ask Assertive,” tending to use more indirect methods of influencing. At the other end, people are more “Tell Assertive,” preferring more direct methods of influence.

Responsiveness is defined as the way a person demonstrates his or her feelings and emotions when interacting with others. At one end of the scale, people are “Task-Directed Responsive,” tending to control their emotions and focus more on the task at hand. At the other end, people are more “People-Directed Responsive,” preferring to express their feelings and focus attention on relationships that affect the task.

Style is derived from the measures of Assertiveness and Responsiveness. Combining Assertiveness (Ask or Tell) and Responsiveness (Task-Directed or People-Directed) creates a matrix whose parts represent the Social Styles (Driver, Expressive, Amiable, Analytical). Social Style is a relatively stable characteristic of a person, meaning that it does not change much over time.

Style is derived from the measures of Assertiveness and Responsiveness. Combining Assertiveness (Ask or Tell) and Responsiveness (Task-Directed or People-Directed) creates a matrix whose parts represent the Social Styles (Driver, Expressive, Amiable, Analytical). Social Style is a relatively stable characteristic of a person, meaning that it does not change much over time.

Versatility is defined as a person’s ability to temporarily modify his or her behaviors to make others feel that their concerns and expectations are being met. Versatility is measured separately from Social Style and, unlike Social Style, is a skill that can be learned. In fact, we have research indicating that learning Versatility will improve individual and organizational performance.

Versatility is the key skill of effective work relationships. People who have learned to recognize when others are uncomfortable or tense in the relationship, and adapt their Assertiveness and Responsiveness to reduce this relationship tension, have more effective interactions with others, resulting in more effective decisions and actions.

All of the dimensions are measured on a continuous scale. That is, no one person is all Ask or all Tell Assertive (or all Task- or People-Directed Responsive). Everyone demonstrates different degrees of Ask and Tell Assertive behaviors. Similarly, while the four Social Styles are a convenient way to describe information about communication patterns, there are varying degrees of style as well.

The Study

Since the inception of Wilson Learning’s Social Style Profiling System in 1975, well over seven million respondents have completed some form of the instrument. For this study, we used a data sample of 165,515 profiles. This sample was chosen to ensure that the analysis represented a relatively equal and unbiased global perspective. While we have profiled participants from over 30 countries, this analysis includes samples from only 20 of those countries because we wanted to ensure that each sample included participants from at least four different companies, that each profile was cross-validated by at least three observers, and that each sample was large enough from which to draw statistical conclusions.

Validity and Reliability

This report focuses on Social Style and Versatility results, not validity and reliability results for this global sample. For more detail on the validation process globally, contact Wilson Learning directly. However, for this report, it is important to address two key points:

Adapted, not Translated: The Social Style Profiles for each country were not literal translations of the U.S. English Profile. Rather, each profile was created to accurately reflect the meaning of Assertiveness, Responsiveness, and Versatility in each culture.

Independently Validated: Before engaging in this global data analysis, each Social Style Profile was validated within each country. That is, a questionnaire was developed, a pilot sample collected, and the data submitted to a range of validation statistics (including factor analysis, internal consistency reliability, inter-rater reliability, factor correlations, and demographic analysis). Finally, after validation, the accuracy of the Social Style Profiles was confirmed against observed behaviors.

Creating the Global Database

Once assured that each country’s profile was accurate and reliable, we were then able to combine the data and create the global Social Style database. This was done by examining each item that measures Assertiveness, Responsiveness, and Versatility across all 20 individual profiles and identifying items that matched in terms of meaning and statistical properties. We then standardized all of the items on a common measurement scale and conducted our analysis.

This part of the process assured us that the Social Style concepts, terminology, and statistical characteristics were consistent across the multiple cultures included in the study. For example, the meaning of a score on Assertiveness in one culture was equivalent to the same score on Assertiveness in another culture.

Findings

When interpreting the findings, it is important to keep in mind that the scores are based upon how others, in their own country, rated each other. This is not a case of “foreigners” responding to stereotypes of people from other countries.

Also, the actual score ranges are narrow because of the large size of each country’s sample. Since each country’s data set consists of more than 1,000 responses, the averages will be close together. This is the nature of averages in large data sets. However, that does not limit the usefulness of the differences we have identified. In all cases, there were statistically significant differences among countries on all of the dimensions measured.

Finally, to simplify interpretation, all of the scores were converted to a 100-point scale. This did not alter the relative scores among countries, but merely kept all of the interpretation across the measures consistent.

Global Social Style

Social Style is determined by combining Assertiveness and Responsiveness, so we will examine all of these dimensions together.

Social Style is determined by combining Assertiveness and Responsiveness, so we will examine all of these dimensions together.

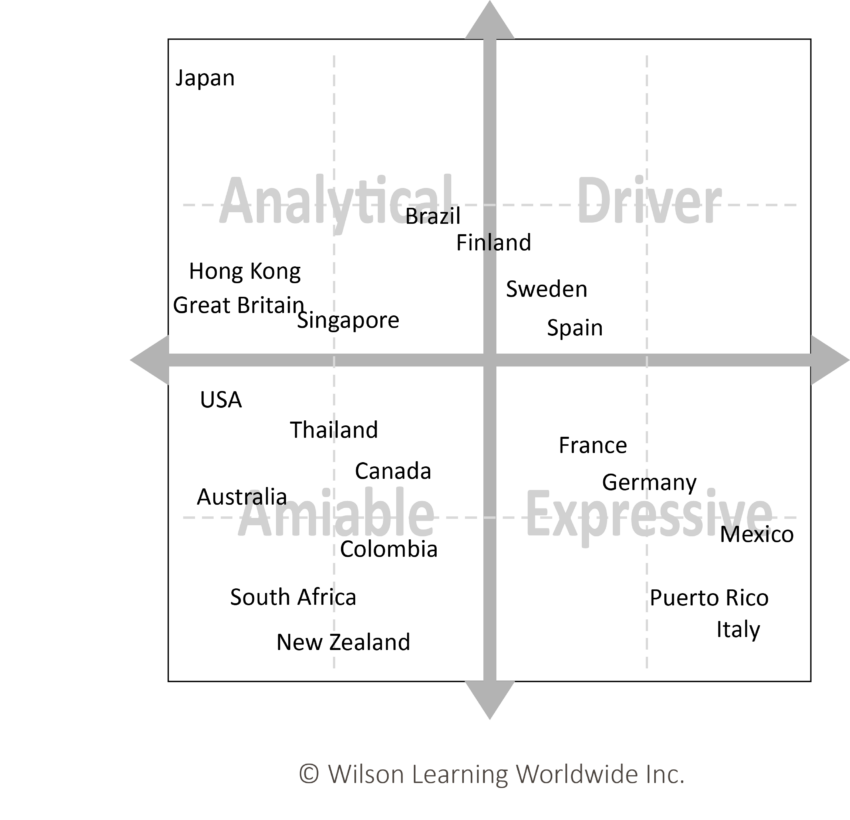

The averages for the 20 countries in the study are plotted on the following Social Style matrix. Location on the matrix does not mean that all individuals in that country are that style; however, it does show how people within that country tend to view themselves relative to other countries. For example, while the average score in Japan is classified as the most Ask Assertive and Task-Directed Responsive (that is, most Analytical), still only 28 percent of the individual participants in Japan were classified as Analytical, just slightly higher than the expected value of 25 percent.

While some of the findings of the research fit with common expectations, others might be surprising.

Many of the Asian country averages fall in the Analytical style classification. That means respondents in those countries tend to view one another as more Ask Assertive and more Task-Directed Responsive. In other words, they were more likely to be perceived as detail-oriented, deliberate, and well organized. Analyticals tend to respond to social overtures rather than initiate them and are more focused on task details, at least early in a relationship.

Many of the Western European and Mediterranean country averages fall in the Expressive style quadrant. That is, people in those countries tend to view each other as more Tell Assertive and People-Directed Responsive. Expressives tend to be perceived as fast-paced, outgoing, and enthusiastic in their interactions. Expressives take time to establish a relationship before focusing on the task at hand. Details tend to be less critical than the big picture for the Expressive.

Countries with more Amiable style averages include the United States, Canada, and Australia. This suggests that, on average, these cultures tend to emphasize cooperation and personal relationships. Amiables tend to see strong, trusting relationships as central to effective business interactions.

Finally, no countries tended strongly toward the Driver style, or high Tell Assertiveness and high Task-Directed Responsiveness. Both Sweden’s and Spain’s averages fall in the Driver quadrant but are closer to the center of the distribution and not at the extremes.

Global Versatility

One of the most important findings of this study is how a culture views its own Versatility. Versatility is a person’s ability to temporarily modify his or her style-related behaviors to make others feel that their concerns and expectations are being met. Unlike Social Style, Versatility is an evaluative dimension. That is, being a particular Social Style is not good or bad—no one style is more successful than another, and no one style is better suited for a leadership position than another. In contrast, Versatility is associated with performance. Our research indicates that salespeople with high Versatility out-sell salespeople with low Versatility. Managers with higher Versatility have better performing work groups than managers with lower Versatility.

One of the most important findings of this study is how a culture views its own Versatility. Versatility is a person’s ability to temporarily modify his or her style-related behaviors to make others feel that their concerns and expectations are being met. Unlike Social Style, Versatility is an evaluative dimension. That is, being a particular Social Style is not good or bad—no one style is more successful than another, and no one style is better suited for a leadership position than another. In contrast, Versatility is associated with performance. Our research indicates that salespeople with high Versatility out-sell salespeople with low Versatility. Managers with higher Versatility have better performing work groups than managers with lower Versatility.

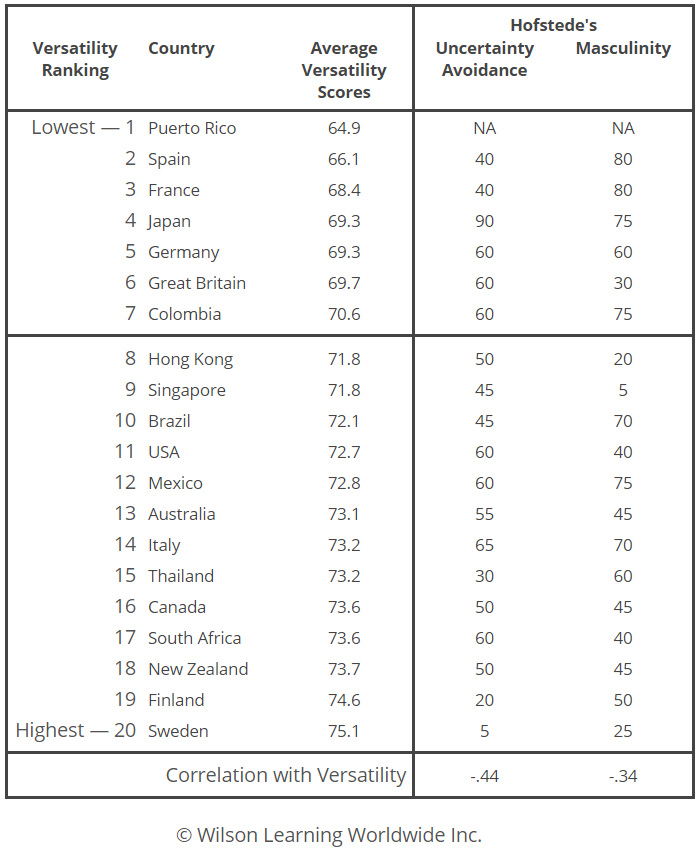

It is reasonable to think that a nation’s level of Versatility might have an impact on its ability to interact on the world stage and be a factor in how its businesses operate globally. The rank order and average Versatility for the different country samples is shown in the first three columns of the following table. It is important to note that, overall, the range of Versatility scores is fairly narrow. On a 100-point scale, all scores fell within an 11-point range. However, even this narrow range between countries is a statistically significant difference.

Looking just at the average Versatility scores column, the results show that Puerto Rico, Spain, and France had the lowest Versatility ratings. Again, that does not mean that all of the people in those countries have low Versatility. There are highly versatile people in all countries, but the averages reflect that there will be more low versatile people in the countries above the median line than in the countries below that line.

Predicting Global Business Effectiveness

Are countries with lower average Versatility more difficult to do business with globally? Our research indicates that individual people who are lower in Versatility are less effective in business, but can that finding be extended to a country’s average Versatility?

While there is no data of which we are aware that compares how easy countries are to work with globally, some insight on Versatility can be gained by comparing Global Versatility scores to other dimensions that have been known to differentiate cultures. One such set of dimensions are those identified by Geert Hofstede’s research on global values. Hofstede’s research is focused on value systems within countries, not intercultural interactions. However, certain cultural values have an impact on how countries view one another as potential business partners. As a result, some interesting comparisons can be made. These comparisons are shown in the following table.

A correlation statistic was used to assess the degree of association between Versatility and the dimensions of Masculinity and Uncertainty Avoidance. Correlations measure the strength of association between two dimensions. Correlations can range from -1.00 to +1.00. Correlations close to 0.0 indicate the two dimensions are unrelated. As they get closer to +1.0 or -1.0, the degree of association increases.

The following table also shows Hofstede’s dimensions of Uncertainty Avoidance and Masculinity. Uncertainty Avoidance focuses on the level of tolerance for uncertainty within the society. High Uncertainty Avoidance indicates the country has a low tolerance for uncertainty; low Uncertainty Avoidance indicates the country has less concern about uncertainty and has more tolerance for a variety of opinions. One would expect a country with low Uncertainty Avoidance to have high Versatility, and that is exactly what we found. The correlation between Versatility and Uncertainty Avoidance is in the moderately high range (r = -.44). The negative correlation indicates that low Uncertainty Avoidance is associated with high Versatility.

The second dimension, Masculinity, is defined as the degree to which a society reinforces the traditional masculine work role model of male achievement, control, and power. Again, you would expect a culture that values power and control would tend to have lower Versatility; again, that is what we found. In this case, the correlation between Versatility and Masculinity is moderate to moderately high (r = -.34).

Thus, a country’s low Versatility is associated with characteristics that might make global interactions more difficult—a low tolerance for varied opinions and uncertainty and a high need for control and power. The difference is that Hofstede’s dimensions are considered cultural traits, unlikely to be changed through learning and development. In contract, Versatility is a learnable skill. Companies operating in countries with lower Versatility may want to examine the level of interpersonal friction that occurs, especially cross-culturally, and take steps to increase their Versatility as a way to grow the economy of their countries.

Changing Global Versatility

In our current global environment, effective cross-cultural work relationships are critical. Global work teams have become commonplace, and while language and cultural differences create their own barrier, a potentially greater barrier is differing expectations about interpersonal communication. At a time when world tensions are high, every individual, organization, and country would be well served to seek out any mechanism possible that will ease tensions and create effective communications.

Global Versatility is not a trait or value of a country. Rather, it is a learnable skill. We have found that if people follow a simple process, they can improve their interactions globally, create a more comfortable work environment, and, as a result, conduct business and social interactions more effectively and more productively.

The first step in becoming more Globally Versatile is recognizing that it requires a mindset shift and a skill set shift. Global Versatility starts with the desire to make people from other cultures and countries more comfortable in their interactions with you and a new awareness that what makes you comfortable in interactions may make others uncomfortable.

Following the mindset shift comes the skill set shift. We have found that the primary skill of Global Versatility can be summarized in a four-step process:

- Anticipate: By knowing the other person’s, and your own, dominant culture, you can anticipate potential barriers to communication, while avoiding the tendency to stereotype. Remember, just because one Social Style might dominate a culture does not mean everyone is that style.

- Identify: The next step is to clarify whether the anticipated behaviors are real. Observe the other person for indications of his or her style. Is the person’s behavior more Ask or more Tell Assertive? Is the person more People-Directed or Task-Directed?

- Reflect: After identifying another’s Social Style, reflect on what will make him or her more comfortable and the type of adjustments you need to make to increase the other person’s comfort level. Consider both Social Style-related behaviors and culture-specific behaviors.

- Modify: Then, make an effort to adjust your Assertiveness and Responsiveness behaviors. Modifying is more than just adjusting; it also requires observing reactions. Did your efforts to modify your behavior have the intended effect? If not, re-examine your behavior. Did you adjust too much or too little? Did you modify the wrong behaviors?

Conclusions

This research suggests that one important mechanism for improving international relationships is Global Versatility. By understanding and identifying the Social Styles of others, learning new behaviors for adjusting Assertiveness and Responsiveness behaviors, and continuously improving Versatility with others, individuals can work more effectively cross-culturally and can improve organizational and individual performance. These findings will enable companies to use the concept and skills of Global Versatility to move across cultural boundaries, work more effectively globally, and better serve customers around the world.